With his short-lived racing career in the past as well as a pending divorce from his first wife, whom he met while living in Laramie and married in 1953, Bill decided he didn’t want a desk job with the state of Wyoming for the rest of his life. He decided he needed to change careers. He knew he liked being a mechanic better than anything else, but he didn’t want to lie on his back under a dirty old car for a career. Bill ‘deductively’ decided a mechanical engineer must be a high-class mechanic, and that was the right choice for him. “I determined I had to go to college,” says Bill. “I traded off my new car, took a semester of advanced algebra at the local high school to qualify, and started putting money in the bank for tuition. At that time I was paying $30 per month for a furnished room, and $2 per day for food. I was taking home about $300 per month, so I could save about $150 per month.”

Bill was serving with the Wyoming National Guard at the time but would not be able to rise above the rank of Master Sergeant in his current role. In 1957 he quit his job with the Adjutant General, so he could be promoted to second Lieutenant and go to artillery school before college. “I was now an officer and assigned with my high school friend, Jim Hawk, to a new artillery unit in Cheyenne. We attended the artillery school together, and I graduated in the top 5 of my class, and second in Gunnery, which was the toughest phase. I was very proud of this accomplishment, as many Wyoming guardsmen before me had failed Gunnery.”

In addition to Howell’s interest in cars, he also grew fond of firearms and weaponry during his tenure in the National Guard. “In my lifetime, I have fired a variety of rifles, pistols and cannons,” says Bill. Starting with his Daisy BB gun, on to a 22 rifle, 30-30 Winchester carbine, 30.06 army rifle, 30 caliber carbine, 35 Remington automatic, several 12-gauge shotguns, several pistols including a 45 caliber automatic, 50 caliber machine gun, as well as the 75mm, 105mm and 155mm howitzers, both trailed and self-propelled. In 1956 Howell was selected along with six others to represent the Wyoming National Guard at the national pistol matches at Camp Perry, Ohio. “I didn’t get selected for my skill, but instead, because I was available and I had a blast learning to shoot a 45 automatic pistol. While there, I took a ferry boat across Lake Erie to Leamington, Canada and had the opportunity to go to a USAC sprint car race at new Bremen, Ohio. It’s a trip I have never forgotten,” says Bill.

In 1957, with $2000 in his savings account, Bill moved back to Laramie to go to the University of Wyoming, and lived with Ken and Arvilla Shappell, his ex in-laws. During his college studies, Bill was also looking ahead to future employment opportunities and seeking jobs while in college. Among his outreach he had sent resumes to several automotive companies, ironically none to Ford or Chrysler. He received a favorable reply from Chevy Engineering in Warren, Michigan. Both John Deere (Dubuque, Iowa) and Chevrolet (Detroit, Michigan) flew Bill to their HQ locations for personal interviews. As a fairly obvious choice, when Chevy offered Howell the job, he accepted immediately, choosing cars over tractors.

“The trip to Dubuque was my first experience with commercial flying, and I flew to Chicago via a DC-6 with four propeller engines. It was noisy and took forever; nothing like current jet travel. This all occurred in November and December 1960, providing me the assurance of a job by the year’s end.”

During his years in college, Howell learned to arc and gas weld, run basic machine tools and a lathe, and as a senior classman, he completed his power lab project on an engine dynamometer. “It was an old flat head Ford V-8 hooked to an electric Dyno,” says Howell of his senior project, “comparing gasoline vs. methanol fuels. I suggested the project to my advisor, also head of the Mechanical Engineering department, Professor Bob Sutherland. He made me agree to submit a paper to the American Society of Mechanical Engineers describing the project before he would approve it.” The mandate turned out to be a beneficial move for the college senior, because not only did Bill get an A on the project, he also won the ASME paper contest at UW. He presented the paper at the University of Colorado at Boulder, which he also won and thereby received an all expenses paid trip to LA in June 1961, to present his paper there as well.

“Since the Chevy dealer in Laramie had let me take possession of my new Corvette at the time, Professor Sutherland and I took it to LA for the ASME contest, and we had a great time. We hit Las Vegas at 4 o’clock in the morning and were awestruck by the lights. As we approached, we could see the Vegas brightness popping out of the desert surroundings, from at least 50 miles away. We also went to Disneyland, which was fairly new then. This was my first exposure to smog in LA, which was horrible at the time. It dimmed the sun, almost like a cloudy condition, and burned your eyes and nose. Coming down the hill into San Bernardino from Las Vegas, the whole valley that was Los Angeles and now the inland empire, looked like it was in a fog bank. On the return trip through the hot desert, with no air-conditioning, we learned that cold watermelon was a better thirst quencher than water or soda,” says Howell.

After graduating mechanical engineering at the University of Wyoming in 1961, Bill kicked off his automotive influence as a novice engineer at Chevrolet. His legendary tenure spanned from 1961 to 1987, operating as one of the core team members in the development of the new big block Chevy motor (replacing the 409). Literally, in this case, a design with 8 cylinders of unique layout formed in the minds of designers and engineers at General Motors creating a big block engine that would produce more muscle in the cars coming off the line in Detroit. Bill was knee-deep in the history-making endeavors to do so. “Because of my intense interest in these types of engines, I was able to do a good job, and my whole time spent as a test engineer was in high-performance engine development.”

Bill Howell began his career at General Motors as an apprentice for Chevrolet Engineering on the dynamometer, where he learned all of the products from one end to the other via GM testing and development. “From July of 1961 to July 62, I apprenticed in the engine dyno cells, at a salary of $500 per month” says Howell, of his startup with the company. “I started by learning the standard GM engine tests and getting acquainted with all the various Chevrolet engines and test facilities, in both development and durability. We had 21 dyno cells at Chevy, with durability dyno cells typically running 3 shifts, 24 hours a day and on Saturday. Development ran one or two shifts depending on the urgency of development.”

And while GM had officially exited racing development in 1957, much of the influence from NASCAR played into their schema for design and horsepower fitting the engine into Corvettes and Camaros and full sized cars. Bill says that at the time, “The Mark I 409 was running a Carter AFB, the biggest carburetor that Carter made in a 4-barrel. The engine made about 425 horsepower,” (as measured on the dyno back in 1961, which would be less by today’s standards). Built originally as a truck motor, Chevy’s 409 didn’t adapt well as a passenger or performance engine.

After only one year working in the dyno cells, Chevy needed a test engineer for the newly designed V-8 engine, and they promoted Howell to test engineer. “It was a dream job that I could not have anticipated,” says the Chevy newbie, at the time.

Bill explains that the test engineer wrote up the instructions for the engine test to be performed, analyzed the data, and then determined what to test next, in coordination with the wishes of the design engineer. “This was a job from heaven, as all the early development on the engine was as a racing variant, and mechanical lifter 427 CID that would be eligible to race in NASCAR if the ‘big wheels’ in management decided to.”

Assigned to oversee development of their next big block engine, designated the MK II, Howell was entrenched in the urgent Chevy program running two shifts and Saturdays. “Initial concept for the engine was maximum power,” says Howell, “designed to be legal under current NASCAR rules. This program introduced Holley carburetors, high-performance mechanical lifters, tuned exhaust with 4 pipes to a collector on each bank, fresh air from vehicle cowl, and high overlap camshafts, plus an increase to 12:1 compression ratio and 427 cubic inches of displacement. In all, we gained 125 BHP and 400 RPM increase in the operating range.”

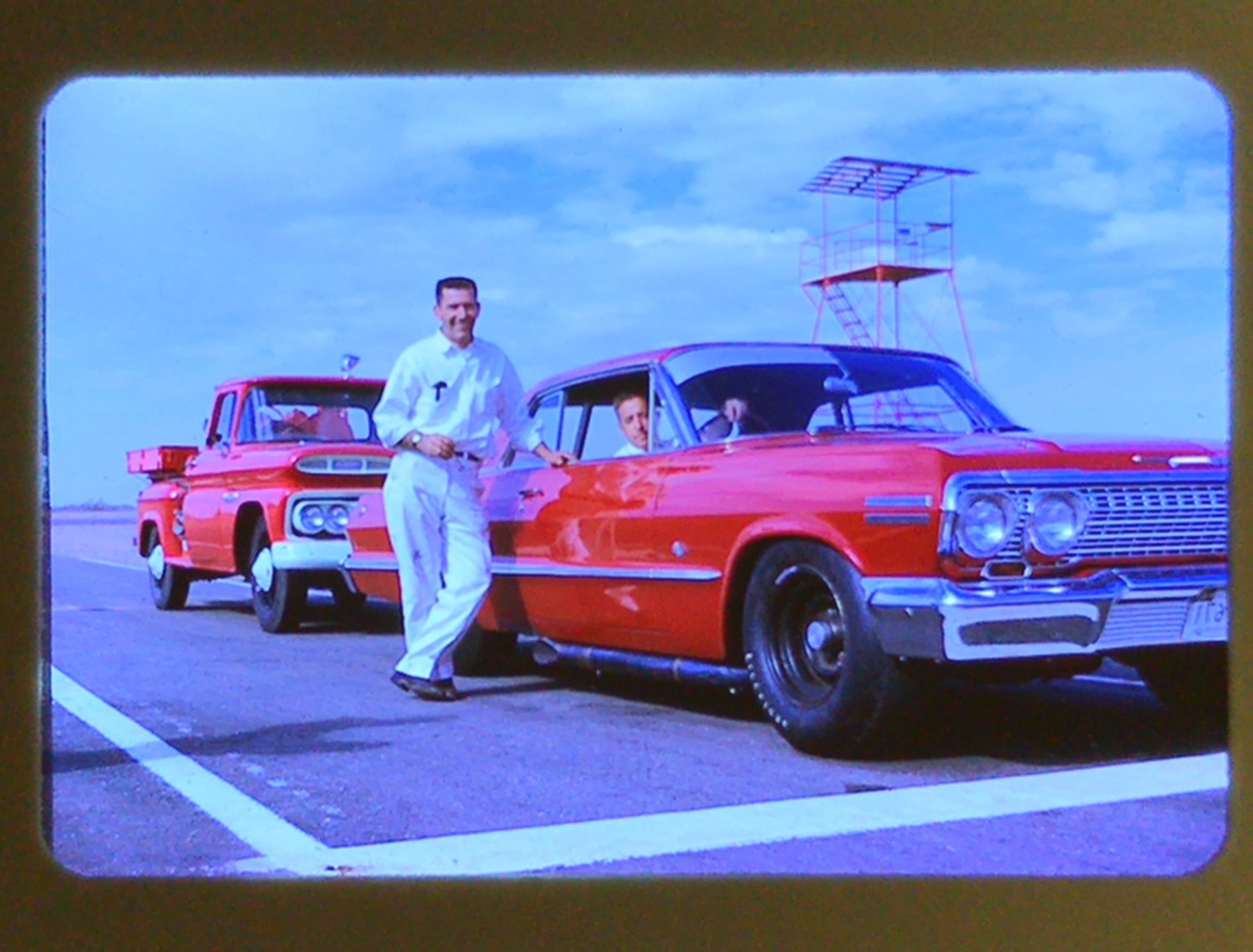

In November of 1962, the Chevy collective spent three weeks testing at their 5-mile circle test track at GM’s desert proving grounds in Mesa, Arizona. Bill and Rex White’s team members dropped the new 427 in the modern-day NASCAR vehicle, a 1963 Impala, built and maintained by Rex White and crew. “From the 409 baseline of 157 MPH, we worked up to 173 MPH,” says Howell.

Along the way his team discovered a number of parameters that needed improvement such as mixture distribution, compression ratio, carburetor design, air filter design, etc. that kept them busy through the end of 1962.

Once the improvements were completed, they returned to the Desert PG in January of 1963, running durability testing to verify their work. “We were now at 177 MPH,” says Bill, “and we ran 430 miles at full speed before experiencing a valve train failure due to a defective chrome coating on an intake valve causing it to stick.”

In addition to the increased volume of the engine’s pistons, Bill says, “the basic difference from the 409 was that the decks were now at right angles to the bores. The cylinder heads had the valves arranged like the later Mark IV design, where they come in at two angles instead of just straight in and down into the bores.” Howell continues, “The Mark II’s originally had the same crankshaft, main and rod-bearing diameters as the 409 engine. Also, you couldn’t swap heads from side to side. They were designed with a right and a left orientation. We kept developing that engine right up into 1964, then we started development of the Mark IV.”

In 1963, team Chevy supplied engines to Ray Fox, Smokey Yunick, and Rex White for their Daytona Race cars. Howell says, “An engine also went to an independent competitor named Farr, one to Ford Motor Company, and two were used by Mickey Thompson in two special pre-production Corvettes for a preliminary Daytona race in early February. I was not involved in the race programs at this time, however, I paid my own way to Daytona to see the results. Only one car (Yunick’s) completed the race, and it was a lap down due to a minor spin out.” Howell continues, “There were probably 15 of our engines running in NASCAR over that summer. As people wore them out, Chevrolet was not allowed to provide additional engine parts. Junior Johnson (Ray Fox car) was the only one to complete the season in 1963, and won the championship with a Mark II. But that was pretty much the end of it until GM officially returned to NASCAR around 1972.”

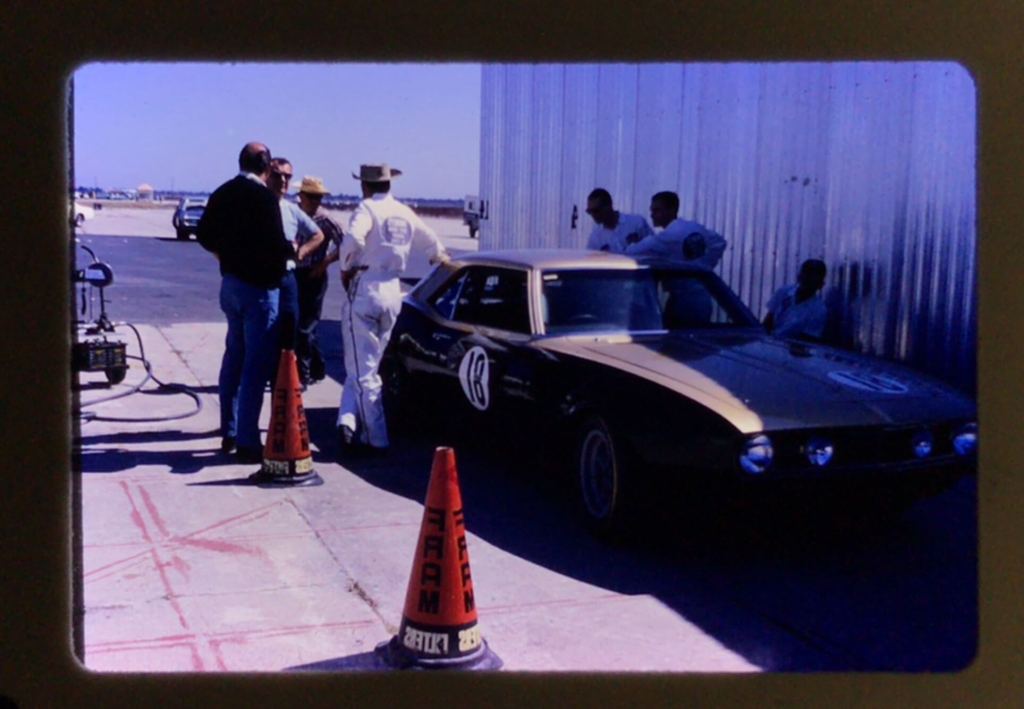

Further supporting Chevy’s official exclusion from racing, corporate followed with a mandate in 1963 to focus on intermediate sized cars restricting engines to 400 CID maximum. Rumors were spreading that NASCAR was going to a 396 cubic-inch limit, and Chevy’s engine group started building the Mark II as a 396. “This put us at about the 515 BHP level. Yunick built a NASCAR spec prototype 1964 Chevelle and we tested it at Fort Stockton, Texas (Firestone test track) in the fall of 1963. It ran 178 MPH with Firestone contract Indy car driver, Chuck Hulse, driving.”